The other day, I proposed that the solution to

making a setting mysterious is to develop in on and around some form of pattern.

From this, I offer that there are at least three levels of patterns: recurring, predictive, and systemic.

A

recurring pattern means that similar things happens several times. This

is the lowest level of a pattern, since if offers very little

information to the player-characters except the realization that they

have had similar experiences before. Basically, a recurring pattern is

what happens if you never say "orc" and the player-characters figure out

that it is in fact an orc they are encountering. This allows them to

rely on proven tactics, thus making them more expert at survival. To

have this type of pattern, all you need to do is to make sure that not

everything in the setting is unique.

The recurring

pattern only involves the PCs through reaction: they encounter the orc,

they realize that it is an orc, and then they can apply their knowledge

to overcome the obstacle. What I call a predictive pattern instead

allows proactivity. It means that the player-characters can use their

understanding of the setting to extrapolate results. They might figure

out that the encounter table is weighted so that their next encounter

will probably be an orc, or that the attack pattern of the dragon means

it will use its its breath weapon in two rounds. Or, as in Isle, they

might figure out where the next magic-user lives and who they are.

Note

that this is not the specialized knowledge of rumors or similar

information, but has much more to do with the general accumulation of

information through experience. To include this type of pattern, you

need to make sure that not everything in the setting is unique, and that

there's some - any - logic to where and when things happen.

The

third level of patterns are systemic. By this I mean that they enable

the player-characters to form predictions not only about what will

happen, but why. In other words, they sense the underlying logic

of how and were systems are applied. It occurs to me that this is a

large part of the appeal of the appeal with builds and combat-as-sport:

you might become so intimately familiar with the system that you know

with confidence that the party can push through an additional four

encounters - any encounters - without any real risk. So the kick comes

not from threat to the character or exploring the unknown, but from

seeing whether your estimates were correct. Like a mars landing: did the

feet-to-meter conversion check out? If not, were the backup systems

robust enough to still ensure victory? Point is: in these types of

games, you can and is rewarded for cracking the system. In an OSR

context, this is generally not something desirable. So if we want this

kind of pattern, it has to be part of the setting. But if I'm correct,

the consequence is that one cannot start the campaign with a city, two

dungeons and a random encounter chart. Instead, the pattern must come

first.

I don't really have a solution to how to do this. But my gut feeling is that you do it by revealing the setting through random encounter tables, connected items, landmarks and other things that are experienced in play and not in a "the story so far"-chapter. Or more generally: by presenting the consequences of your ideas, rather than the ideas themselves. At least, that's how I'll try to approach it for my next campaign.

onsdag 21 februari 2018

söndag 18 februari 2018

Patterns, or Lessons from Isle of the Unknown

In many ways, Isle of the Unknown is a mediocre module at best. Its descriptions do little more than state that something is there, and content is repetitive and highly formulaic, as if procedurally generated from a

limited set of items. And unlike Carcosa which benefits from a novel setting, Isle of the Unknown is essentially a French medieval island. Thus, it would be tempting to write it off as a dud existing only to meet a hexcrawl quota. But to me, the

module is remarkable in how it presents you with the illusion of depth and meaning.

I would argue that the formulaic elements conjure up a specific setting that the

player-characters gradually learn to anticipate and understand.

This is especially true for the magic-users that scatter the island. In Isle, it is fully possible (albeit

improbable) to figure out both the location and overall theme of the not-yet encountered magicians once a few of them have been found.This alone makes Isle rather unique. But furthermore, the player-characters might even happen upon an encounter that explains the existence of some of the formulaic elements, thus

enabling them to intuit some form of history for the setting itself. Now granted, the revelation is far from mind-boggling. But there is a "there" there, build into the adventure at a structural level and reflected in construction of the book. This makes

Isle - flaws and all - one of the landmark modules of the OSR. It is designed to contain something more than what meets the eye.

A mystery.

One of the ideas that spoke most to me in the early OSR was that fantasy games had lost track of the fantastical. The more we play, the less is left unexplained. We have already fought a vampire, we know the HD of a goblin, and so on, and we are worse for it. Hence, the call to arms was to reintroduce mystery and a sense of wonder! And as soon as the problem had been outlined, so were its solutions, such as

- Don't speak in game terms.

- Use unique monsters, or at least pretend that they are unique by describing them instead of naming them.

- Go for weird instead of vanilla.

- Use pulp as inspiration, not Tolkien. And so on.

These are all good to very-good advice. But to me, they miss something fundamental. Neither of the standard solutions create MYSTERY. What they do is create uncertainty. Their idea is to replace some of the known with something unknown, or to recast the familiar as something unfamiliar. But at least to me, mystery is something completely different.

Mystery, I'd say, is the recognition of a logic that you cannot (yet) understand. It's a secret you can uncover, engaging a system that just might be there. A pattern. If this is true, then uniqueness and weirdness might, in themselves, actually be counterproductive. If the setting is systematically strange, it stops being unknown and becomes unknowable.

Following the cue of Isle, I'd argue that the solution to making a setting mysterious is not just to replace the ordinary with the extra-ordinary but to provide the extra-ordinary with its own pattern.

A mystery.

One of the ideas that spoke most to me in the early OSR was that fantasy games had lost track of the fantastical. The more we play, the less is left unexplained. We have already fought a vampire, we know the HD of a goblin, and so on, and we are worse for it. Hence, the call to arms was to reintroduce mystery and a sense of wonder! And as soon as the problem had been outlined, so were its solutions, such as

- Don't speak in game terms.

- Use unique monsters, or at least pretend that they are unique by describing them instead of naming them.

- Go for weird instead of vanilla.

- Use pulp as inspiration, not Tolkien. And so on.

These are all good to very-good advice. But to me, they miss something fundamental. Neither of the standard solutions create MYSTERY. What they do is create uncertainty. Their idea is to replace some of the known with something unknown, or to recast the familiar as something unfamiliar. But at least to me, mystery is something completely different.

Mystery, I'd say, is the recognition of a logic that you cannot (yet) understand. It's a secret you can uncover, engaging a system that just might be there. A pattern. If this is true, then uniqueness and weirdness might, in themselves, actually be counterproductive. If the setting is systematically strange, it stops being unknown and becomes unknowable.

Following the cue of Isle, I'd argue that the solution to making a setting mysterious is not just to replace the ordinary with the extra-ordinary but to provide the extra-ordinary with its own pattern.

måndag 12 februari 2018

1 page adventure: Gerait Demon Keep

There's a ton of good adventures for D&D and other fantasy games. However, most of them are set underground. This is a problem for me, since I'm easily bored with the dungeon as an environment, and consequently planning a campaign mostly set above ground. But then it occurred to me that perhaps other people feel the same way, or at least feel that dungeon-style adventures set above ground could be a nice complement to the regular dungeons.

Thus, I present Gerait Demon Keep. Like with Luthria convent, the idea is to

keep it short,

include some measure of loot,

hint on a setting; and

provide a clue for further adventures (here, in the form of books and a map that could lead to a new adventure site).

Enjoy.

Thus, I present Gerait Demon Keep. Like with Luthria convent, the idea is to

keep it short,

include some measure of loot,

hint on a setting; and

provide a clue for further adventures (here, in the form of books and a map that could lead to a new adventure site).

Enjoy.

fredag 9 februari 2018

2 page adventure: Luthria convent

A convent occupied by a hostile force. Focus is on social interactions, mystery and stealth. A small adventure location for my campaign. I need to pick up speed and make many more.

onsdag 7 februari 2018

Mysteries: Spellcasting

Whitehack casting (free-from effects, payed for by HP loss), with the following modifications

1. Magic draws the attention of demons, and worse. When casting a spell, roll 1d20 and notify the referee of the result.

2. A character can combine any two spells to temporarily create a new. The new spell name must contain one word from each spell it draws upon. An "of", a genitive-s, or similar minute alterations might be added to better connect the words. Casting a hybrid spell requires you to roll 1d20 twice and notify the referee of the results.

(Some names might be too weak or too powerful, I might have to adjust that)

WILDERNESS

Swarm Skin

Weed Mask

Lash of Thorns

Beast Sense

Locust Storm

Moss Gate

DISEASE

Bestial Blight

Serpent's Dementia

Fever Crown

Worm Mouth

Putrid Gust

Catatonic Stupor

DEATH

False Life

Blood Altar

Corpse Dust

Eldritch Effigy

Repelling Voice

Feigned Death

SPIRITS

Ghost Flare

Grave Tongue

Spectral Stride

Luminous Stalker

Phantasmal Dispersion

Spirit Warden

DEMONIC

Shadow Throne

Threefold Path

Sign of Many

Plasmic Key

Unspeakable Oath

Dismal Presence

ENCHANTMENTS

Twisted Valor

Consuming Lust

Heart of Wax

Rending Clamor

Fool's Eye

Strange Recollection

COLD

Frost Grasp

Glacial Crust

Treacherous Mist

Hall of Water

Suspended Flow

Ice Cloud

NIGHT

Mercurial Dread

Creeping Tide

Moon Song

Tranquil Light

Spiral of Moths

Vale of Obscurity

HEXES

Oracular Incense

Spider Jar

Soul Eye

Fay Leap

Shroud of Thralldom

Dissonant Whisper

FIRE

Sustained Flame

Fire Blade

Static Spark

Ash of Lament

Sulfur Gale

Guiding Glow

DIVINE

Blessed Bane

Timeless Echo

Resonating Wings

Unseen Hand

Hallowed Flesh

Zealous Plight

SIGNS

Illusory Script

Silent Image

Glyph of Warding

True Sight

Delusive Mark

Lure of Oblivion

1. Magic draws the attention of demons, and worse. When casting a spell, roll 1d20 and notify the referee of the result.

2. A character can combine any two spells to temporarily create a new. The new spell name must contain one word from each spell it draws upon. An "of", a genitive-s, or similar minute alterations might be added to better connect the words. Casting a hybrid spell requires you to roll 1d20 twice and notify the referee of the results.

(Some names might be too weak or too powerful, I might have to adjust that)

WILDERNESS

Swarm Skin

Weed Mask

Lash of Thorns

Beast Sense

Locust Storm

Moss Gate

DISEASE

Bestial Blight

Serpent's Dementia

Fever Crown

Worm Mouth

Putrid Gust

Catatonic Stupor

DEATH

False Life

Blood Altar

Corpse Dust

Eldritch Effigy

Repelling Voice

Feigned Death

SPIRITS

Ghost Flare

Grave Tongue

Spectral Stride

Luminous Stalker

Phantasmal Dispersion

Spirit Warden

DEMONIC

Shadow Throne

Threefold Path

Sign of Many

Plasmic Key

Unspeakable Oath

Dismal Presence

ENCHANTMENTS

Twisted Valor

Consuming Lust

Heart of Wax

Rending Clamor

Fool's Eye

Strange Recollection

COLD

Frost Grasp

Glacial Crust

Treacherous Mist

Hall of Water

Suspended Flow

Ice Cloud

NIGHT

Mercurial Dread

Creeping Tide

Moon Song

Tranquil Light

Spiral of Moths

Vale of Obscurity

HEXES

Oracular Incense

Spider Jar

Soul Eye

Fay Leap

Shroud of Thralldom

Dissonant Whisper

FIRE

Sustained Flame

Fire Blade

Static Spark

Ash of Lament

Sulfur Gale

Guiding Glow

DIVINE

Blessed Bane

Timeless Echo

Resonating Wings

Unseen Hand

Hallowed Flesh

Zealous Plight

SIGNS

Illusory Script

Silent Image

Glyph of Warding

True Sight

Delusive Mark

Lure of Oblivion

tisdag 6 februari 2018

The Case for Squares

One of the issues with hexagons is that they tend to be the wrong size. Now, of course you can choose to have smaller or larger hexagons, but the thing is that no matter which size you ultimately settle on it's not optimal for all purposes. Part of this is that the natural unit of a map is distance, while the natural unit of travel is time and the unit of exploration is line-of-sight. Thus, plain-hexes could reasonably be much larger than jungle-hexes.

Another part is encounter density. To more accurately represent your setting, the solution is to zoom in. But once you do that you get a crazy number of hexes to fill which a) renders you a massive amount of work; b) tempts you to cheat the players of their agency by having totally random contents (like MYZ); and/or c) creates a strange pace when players by chance repeatedly choose the unpopulated hexes.

A basic cause for these problems, I would argue, is that space gamified through hexagons conflates unit of movement (ie. "move one hex") with points of interest (ie. "in this hex, there is..."). Or in other words, hexes scale poorly. There are solutions for dividing a hex into smaller sub-hexes, but they aren't very practical.

On the basis of this, I want to suggest another way: to treat the game-map as if it was a normal map. I have yet to playtest this, so there might be some hidden flaw, but since rules are often more complicated than relying on prior knowledge I think it might carry some merit.

The idea is this

Instead of superimposing hexagons on your map, you place a square grid.

This square grid does not primarily represent spaces in a game sense (as in: move your pawn two spaces) but a coordinate system.

Make the scale so that 1 square is 1 (metric) mile square in reality, but 1 cm2 on the map.

Set base movement to 3 miles in light terrain.

Use a ruler.

This has the following consequences

For MOVEMENT. The party can move 3 squares horizontally or vertically, OR that they can move 3 cm in any direction they want. So a novice group would probably stick to the orthogonal, whereas a more experienced group would say "we travel NNE for eight miles, then turn sharp E for another seven to stay clear of the Dragon valley"

for SCALE. You could zoom in and out as you like. Each square can be divided into 10x10 new squares (each 1 km) or 100X100 (each 100 m), and each 100 squares in turn form a macro square (10 x 10 miles) and so on. And as long as you keep this basic structure, your coordinates will work. As an example, East 20,0 through East 20,9 would be the ten horizontal locations nested within square East 20. And East 20 through 29 would in turn be part of the macro-hex East 2X.

for ENCOUNTERS. Since the location of anything on the map can be stated as precise as your ruler allows, you could vary the encounter area for each encounter. A hidden cache is perhaps only found is the party moves into the exact dot representing it on the map, whereas a city is encountered in the square and a prowling beast in encountered within a four mile radius of its lair.

for LEGIBILITY. Normal coordinates are much easier to track than hex-coordinates. There's no need for numbers in every square - making every fifth gridline thicker and having numbers every tenth would suffice. This allows much more room for at-a-glance information on the referee's map.

Obviously, there are strong reasons for sticking with hexagons. They look good. They rest on a strong tradition, and form the basis for many procedures. They have an esoteric quality that sets game-specific knowledge apart from normal knowledge. Etc. On the other hand, I think that there's a solid case for squares.

Another part is encounter density. To more accurately represent your setting, the solution is to zoom in. But once you do that you get a crazy number of hexes to fill which a) renders you a massive amount of work; b) tempts you to cheat the players of their agency by having totally random contents (like MYZ); and/or c) creates a strange pace when players by chance repeatedly choose the unpopulated hexes.

A basic cause for these problems, I would argue, is that space gamified through hexagons conflates unit of movement (ie. "move one hex") with points of interest (ie. "in this hex, there is..."). Or in other words, hexes scale poorly. There are solutions for dividing a hex into smaller sub-hexes, but they aren't very practical.

On the basis of this, I want to suggest another way: to treat the game-map as if it was a normal map. I have yet to playtest this, so there might be some hidden flaw, but since rules are often more complicated than relying on prior knowledge I think it might carry some merit.

The idea is this

Instead of superimposing hexagons on your map, you place a square grid.

This square grid does not primarily represent spaces in a game sense (as in: move your pawn two spaces) but a coordinate system.

Make the scale so that 1 square is 1 (metric) mile square in reality, but 1 cm2 on the map.

Set base movement to 3 miles in light terrain.

Use a ruler.

This has the following consequences

For MOVEMENT. The party can move 3 squares horizontally or vertically, OR that they can move 3 cm in any direction they want. So a novice group would probably stick to the orthogonal, whereas a more experienced group would say "we travel NNE for eight miles, then turn sharp E for another seven to stay clear of the Dragon valley"

for SCALE. You could zoom in and out as you like. Each square can be divided into 10x10 new squares (each 1 km) or 100X100 (each 100 m), and each 100 squares in turn form a macro square (10 x 10 miles) and so on. And as long as you keep this basic structure, your coordinates will work. As an example, East 20,0 through East 20,9 would be the ten horizontal locations nested within square East 20. And East 20 through 29 would in turn be part of the macro-hex East 2X.

for ENCOUNTERS. Since the location of anything on the map can be stated as precise as your ruler allows, you could vary the encounter area for each encounter. A hidden cache is perhaps only found is the party moves into the exact dot representing it on the map, whereas a city is encountered in the square and a prowling beast in encountered within a four mile radius of its lair.

for LEGIBILITY. Normal coordinates are much easier to track than hex-coordinates. There's no need for numbers in every square - making every fifth gridline thicker and having numbers every tenth would suffice. This allows much more room for at-a-glance information on the referee's map.

Obviously, there are strong reasons for sticking with hexagons. They look good. They rest on a strong tradition, and form the basis for many procedures. They have an esoteric quality that sets game-specific knowledge apart from normal knowledge. Etc. On the other hand, I think that there's a solid case for squares.

söndag 4 februari 2018

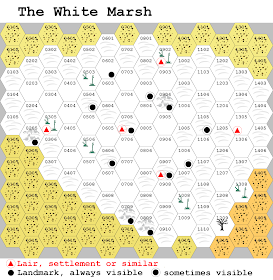

Hexcrawl self-promo

Since I'm writing about overland travel, I might as well point to the small hexcrawl I did last year. I think the format works very well for this kind of "find the lost thing" adventures, since if you're looking for something that you have no clue where it is it makes a lot of sense to proceed slowly, make constant decisions on your course and move without any clear direction.

There is a fancy illustrated version, but also a free PDF here and a docx to facilitate ctrl-replacing monster stats or cutting and pasting the things you like into your own campaign.

There is a fancy illustrated version, but also a free PDF here and a docx to facilitate ctrl-replacing monster stats or cutting and pasting the things you like into your own campaign.

lördag 3 februari 2018

The merit of cascading dice

Cascading dice, popularized by The Black Hack as usage dice, is an excellent mechanic. You roll a die, and on 1 or 2 the die size decreases. When the die is reduced below 1d4, the resource you're using is depleted. It's an elegant rule, its fun, and it produces a nice acceleration of degradation near the end. However, the rule is also often described as making book-keeping easier or simplifying things. For example, one reviewer writes

The disconnect between perceived simplicity and reality becomes even more marked with rations, which haves you roll your die as often as you would otherwise mark one ration used. In other words: usage dice are a simple system for bookkeeping, but primarily in comparison to a hypothesized much more complex system. Any gamer can come up with tremendously complex systems at the blink of an eye. And that is often our point of comparison. But the reality is that any rule, no matter how simple, is often more burdensome than having no rule at all, because through our successful existence as humans we are already stuffed full of systems and procedures for doing any number of things.

So my contention is this:

Even a very simple rule is often more complex than relying on already existing knowledge. Instead, enjoyable rules often serve to gamify aspects that would otherwise seem uninteresting or unappealing. And one of the major ways of doing this is shifting from managing resources to managing risk.

This is why cascading dice works: not because they make book-keeping simpler but that they gamify an aspect that many gamers find all-too mundane, by transforming it into a risk. But beyond that, I would also argue that this is why low-lever combat is very different than high-level ditto, and why many vastly prefer the former. It is also the reason why wandering monster checks are fairly universally applied, whereas counting rations are less so, and why burn-time of torches become a more urgent matter when you throw away all but one to haul as much loot as you can out of the dungeon. For a large subset of gamers, adjusting to uncertainty and gambling on your odds are much more exciting than logistics.

Because of this, i think that the notion of wilderness travel as a game of resource management is very accurate, but also part of why it has found less traction than dungeon explorations and other forms of adventures.

Basically, I think that any system of wilderness exploration should consider which parts to be left alone (without rules), which parts to keep, and which parts to further gamify by shifting focus from resources to risks.

"Every item that has a limited number of uses has a usage die. So, instead of counting every arrow you have, you simply say your arrows have a usage die of d10. Whenever you use the item, you roll the usage die. If you roll a 1 or 2, you step the usage die down. So, if I rolled a 1 on my d10 after firing my bow, I now have d8 arrows. Once you get to d4 and roll a 1 or 2, you are out of whatever the item was. No more marking off each little arrow, torch, etc."What I want to highlight here is that this statement is perfectly valid in an RPG context, yet it is fundamentally weird. If a person who had no prior experience from any game sat down at your table and you said "your bow has ten arrows", they would immediately understand the bookkeeping involved. Shoot one, deduct one. This simplified approach, on the other hand, requires a paragraph to explain.

The disconnect between perceived simplicity and reality becomes even more marked with rations, which haves you roll your die as often as you would otherwise mark one ration used. In other words: usage dice are a simple system for bookkeeping, but primarily in comparison to a hypothesized much more complex system. Any gamer can come up with tremendously complex systems at the blink of an eye. And that is often our point of comparison. But the reality is that any rule, no matter how simple, is often more burdensome than having no rule at all, because through our successful existence as humans we are already stuffed full of systems and procedures for doing any number of things.

So my contention is this:

Even a very simple rule is often more complex than relying on already existing knowledge. Instead, enjoyable rules often serve to gamify aspects that would otherwise seem uninteresting or unappealing. And one of the major ways of doing this is shifting from managing resources to managing risk.

This is why cascading dice works: not because they make book-keeping simpler but that they gamify an aspect that many gamers find all-too mundane, by transforming it into a risk. But beyond that, I would also argue that this is why low-lever combat is very different than high-level ditto, and why many vastly prefer the former. It is also the reason why wandering monster checks are fairly universally applied, whereas counting rations are less so, and why burn-time of torches become a more urgent matter when you throw away all but one to haul as much loot as you can out of the dungeon. For a large subset of gamers, adjusting to uncertainty and gambling on your odds are much more exciting than logistics.

Because of this, i think that the notion of wilderness travel as a game of resource management is very accurate, but also part of why it has found less traction than dungeon explorations and other forms of adventures.

Basically, I think that any system of wilderness exploration should consider which parts to be left alone (without rules), which parts to keep, and which parts to further gamify by shifting focus from resources to risks.

fredag 2 februari 2018

Lessons in wilderness travel from TOR

Prompted by a post by Gabor Lux, I started thinking about (rpg) rules for wilderness travel. Generally, I find I like the idea of wilderness travel better than the actual thing - in all games but The One Ring. Here's what I like about traveling in The One Ring.

First of all, you don't go hex-to-hex, but plot out your journey one leg at a time: from Rhosgobel to Gladden Fields, then upriver to Old Ford, then North to Beorn. Only after having plotted out your course do you check the hexmap and DM maps to calculate distances. This places a substantial overhead on the planning of the journey where you might need to break out your calculator to multiply the hexagons with the terrain difficulty and so on. But the actual activities at the table - deciding on a destination and choosing the best way there - is very closely related to the in-game activity. Because of this, it is neither a chore, nor as abstract and repetitive as the constant choices of direction in a hexcrawl.

Second, there's (room for) emergent complexity in how the various skill tests interact with the specifics of the journey. In TOR, you roll one or more times on your Travel skill during a journey, and in addition there are group roles - like Lookout - that might require players to roll on specific skills. Any character can only hold one role in the group. Consequently, a larger group is better for handling the tasks: having three Lookouts makes you less likely to be ambushed. But at the same time, these specific rolls are often the results of Misfortunes - or catastrophic failures on other die rolls. So the larger group has better chances of handling problems, while the smaller group has better chances of never encountering problems. This is super elegant.

Third, traveling drains your resources without you counting arrows and rations. Instead, you gain fatigue which is related to HP, and gain shadow (the corruption measure) which is related to your succeed anyway-currency Hope. Neither of this affects your character negatively, but they affect the risk associated with your actions. So for example, a character with 10 Hope can turn 10 failures into successes (basically). If the character suffers 8 Shadow, she still has the same potential of turning 10 failures into successes. But once she has done so twice - making her Hope no higher than her Shadow - any catastrophic failure will result in an act of cowardice, greed or similar anti-social behavior. This concentrates book-keeping but also introduces tensions in the group simply because you can see the odds worsen. Far from superficial role-playing cues, you act on your knowledge that the tired fighter has gone from a bedrock to a liability in his current state.

Fourth, following paths you've traveled before significantly reduces travel time. Again, this is reflected both in the rules, in the planning (you know which way to go) and in the calculations (you know how many hexes the distance is). So even if you didn't find anything else, this is something that gives your exploration value.

The fatal flaw.

The main shortcoming of TOR is that there is nothing on the map except the obvious. I like the pacing, where you travel for days without seeing anyone. But there should be SOMETHING to discover other than random encounters and major settlements. For such a large map, I think there should've been at least 100 locations that were only on the GM's map for the PCs to encounter on their travels. Worse, the map contains no coordinate system so even crowdsourcing locations is difficult because there's no straightforward way for me to place an idea on anyone else's map.

First of all, you don't go hex-to-hex, but plot out your journey one leg at a time: from Rhosgobel to Gladden Fields, then upriver to Old Ford, then North to Beorn. Only after having plotted out your course do you check the hexmap and DM maps to calculate distances. This places a substantial overhead on the planning of the journey where you might need to break out your calculator to multiply the hexagons with the terrain difficulty and so on. But the actual activities at the table - deciding on a destination and choosing the best way there - is very closely related to the in-game activity. Because of this, it is neither a chore, nor as abstract and repetitive as the constant choices of direction in a hexcrawl.

Second, there's (room for) emergent complexity in how the various skill tests interact with the specifics of the journey. In TOR, you roll one or more times on your Travel skill during a journey, and in addition there are group roles - like Lookout - that might require players to roll on specific skills. Any character can only hold one role in the group. Consequently, a larger group is better for handling the tasks: having three Lookouts makes you less likely to be ambushed. But at the same time, these specific rolls are often the results of Misfortunes - or catastrophic failures on other die rolls. So the larger group has better chances of handling problems, while the smaller group has better chances of never encountering problems. This is super elegant.

Third, traveling drains your resources without you counting arrows and rations. Instead, you gain fatigue which is related to HP, and gain shadow (the corruption measure) which is related to your succeed anyway-currency Hope. Neither of this affects your character negatively, but they affect the risk associated with your actions. So for example, a character with 10 Hope can turn 10 failures into successes (basically). If the character suffers 8 Shadow, she still has the same potential of turning 10 failures into successes. But once she has done so twice - making her Hope no higher than her Shadow - any catastrophic failure will result in an act of cowardice, greed or similar anti-social behavior. This concentrates book-keeping but also introduces tensions in the group simply because you can see the odds worsen. Far from superficial role-playing cues, you act on your knowledge that the tired fighter has gone from a bedrock to a liability in his current state.

Fourth, following paths you've traveled before significantly reduces travel time. Again, this is reflected both in the rules, in the planning (you know which way to go) and in the calculations (you know how many hexes the distance is). So even if you didn't find anything else, this is something that gives your exploration value.

The fatal flaw.

The main shortcoming of TOR is that there is nothing on the map except the obvious. I like the pacing, where you travel for days without seeing anyone. But there should be SOMETHING to discover other than random encounters and major settlements. For such a large map, I think there should've been at least 100 locations that were only on the GM's map for the PCs to encounter on their travels. Worse, the map contains no coordinate system so even crowdsourcing locations is difficult because there's no straightforward way for me to place an idea on anyone else's map.